- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 97,489

https://james-patton.net/2016/04/30...ctions-the-erosion-of-meaning-in-crpg-quests/

Sidequests and other distractions: the erosion of meaning in CRPG quests

[Note: I wrote this a while ago and forgot to publish it. I still think it’s quite interesting, so here we go!]

What is a quest?

A thing to get distracted from.

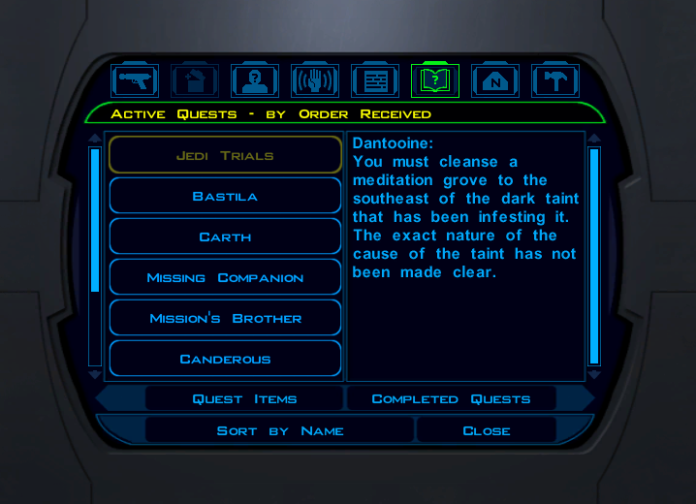

We’ve all been there, whether the game du jour was a Fallout, an Elder Scroll or an Assassin’s Creed, where icons dot the map like tempting candy – or pepper it like buckshot. Replaying Knights of the Old Republic recently I received an important quest: investigate an ominous grove infested with dark energy, a focus of evil drawing things to the dark side. Surely it should have been my number one priority? But I wasn’t at all surprised that it was literally the last thing I did – after working through everything else on my to-do list.

It’s weird that my priorities were “Do odd chores, then do vital Jedi stuff”. But what’s weirder is that this is normal for us. And my problem with it isn’t so much that our heroes act in unheroic ways (“I’ll do my chores, then save the world”) – after all, games are not film etc. and just because a character would act a certain way in one medium doesn’t mean we should crowbar players into acting that way in games. But I do think it leaves a lot to be desired, since it widens the rift between the player, their avatar and the game world.

This is not inherently bad. This juggling of quests and side-quests is, I guess, part of the form of CRPGs, set in stone by the time Baldur’s Gate came along (1998) but present in games quite a bit earlier: you see similar plot/task juggling in, for example, the first-person CRPG Betrayal at Krondor (1993), just on a smaller scale. This “start task, get distracted by other task, end up with a shopping list of stuff” model seems natural to videogames – perhaps because, in giving us a to-do list, the form naturally dovetails with the player’s instinct to tidy up game worlds.

Still, I think videogame “quests” could benefit from quest models from other media: literature, for example. Quests in videogames – particularly RPGs – are promising opportunities for expression, empathy and the creation of meaning: key moments in the role-playing interface between game and player. Yet often they’re repetitious, predictable and by-the-numbers – and even when they’re not, the meaty quests brimming with character are often undercut by popping off to kill 10 spider rats.

So where did this word come from?

I don’t want to draw too firm a line between the word’s shifting meaning and its role in the form of the modern RPG, but I do feel that “quest”‘s changing connotations in videogames reflects the changing role that tasks and assignments played in that medium.

Image from https://www.pinterest.com/pin/324892560593359497/

A quest was, in the literary tradition, a grand task of great personal or spiritual significance. The premier quest narrative is probably the quest for the Holy Grail by the knights of King Arthur: a task of almost impossible difficulty. Naturally, the quest has obstacles: there are enemies to fight, secrets to find and long distances to traverse. But the quest is almost entirely spiritual: only a knight pure of heart is capable of finding the Grail. The quest is not simply a challenge: success or failure is a reflection of the protagonist’s self, their inner worth outwardly shown through accomplishment or failure. A sinful knight will fail not due to lack of ability but lack of worth, whereas a pure knight could stumble onto the Grail by accident. (Except it’s never an accident, because God.) In the Arthurian tradition the grail represents the presence of God and a life spent pursuing Christian values; the knights’ search is an allegory for the pursuit of such a life.

Our usage of “quest” in everyday English is a bit different. Our personal quests aren’t so hardcore, but still demonstrate deep personal significance. A scientist might be on a “quest for knowledge”, a detective on a “quest for truth”. Both represent a strong commitment to a task which is held personally important – even vital – to those who undertake it, and which both arises from and further defines their character: an expression of their most deeply-held beliefs and values. The quest exists because of their character traits (a lazy detective does not go on a quest for truth), but by accepting the quest they further define themselves in terms of those traits (a detective who continues their quest for truth against all odds is more driven, narratively, than a detective who loves truth but never had to go on a quest for it).

Of course, the word has different connotations when it comes to games. (Even with physical games: there’s brand of laser tag called “Laser Quest”.) While the term today is most associated with RPGs, it was originally linked with Sierra adventure games from the ’80s and ’90s like King’s Quest, Space Quest and Police Quest. Sierra borrowed “quest” from the literary tradition to define King’s Quest – “play this game and you will go on a life-changing adventure seeking magical items of spiritual significance” – but the term soon morphed into a brandname signifying “This is a Sierra adventure”.King’s Quest games, with their magical artefacts and fantasy settings, could be considered a quest in the traditional sense; the goofy shenanigans of Space Quest and finicky police minigames of Police Quest seem a bit of a stretch.

Pictured: not really a quest. Image from the Space Quest omnipedia.

Interestingly, “quest” might have been closer to its literary origins in the original Dungeons and Dragons. In the third edition there’s no mention of quests; instead, the handbook refers only to “adventures”. By the fourth edition, however, a typical adventure > major quest > minor quest hierarchy has been established: “Most adventures are more complex, involving multiple quests. A single major quest might drive your adventure. […] Any number of minor quests could complicate that task.” A quest in the third edition must have been a significant personal journey, a quest in the fourth edition only a major or minor task.

I suspect this change came about due to computer RPG terminology, and I suspect that terminology became fixed with the introduction of Baldur’s Gate 2, a pivotal game in the RPG scene. The journal for BG2 is a typical quest-log in the modern sense:

Image from http://lparchive.org/

The top of the journal shows the now-familiar journal format: unfinished quests on the left, finished quests on the right. You may be wondering what this “Journal” button is on the bottom left, though. As far as I can tell this is left over from the original Baldur’s Gate, which had a totally different journal system:

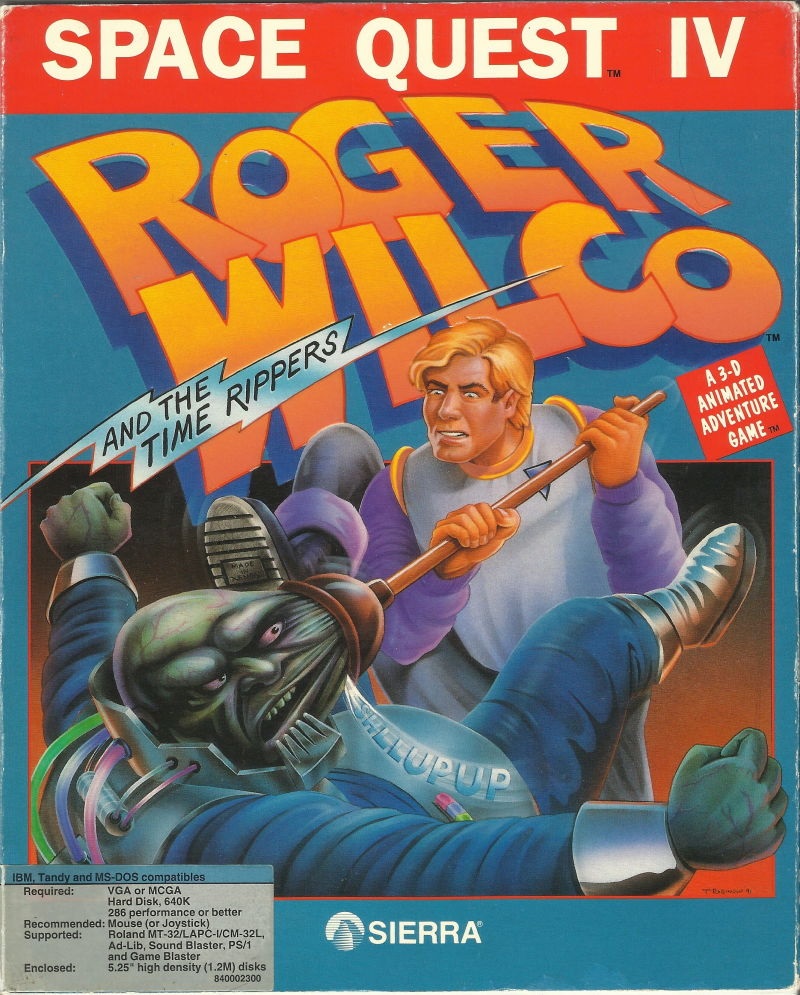

From “Let’s Play Baldur’s Gate – 34 – Marcus’ Journal” by SorcererDave, via youtube.com

In the original Baldur’s Gate journal, quests were not represented: instead players were given a list of date-stamped entries which filled out as their adventure progressed. Their story was told linearly, as a series of diary entries.

I find it interesting that you can see the development of quests and task structures in CRPGs through their evolving interfaces. I also find it interesting that while the BG developers started by keeping track of actions in a journal – a throwback to the storytelling focus of D&D – and kept it as a vestigial interface feature in the sequel, it’s ultimately a forgotten feature which has been expunged from the RPG genre. CRPGs, at least those built on Baldur’s Gate‘s foundations, do not lend themselves to organic storytelling as much as they do to “I completed this goal, I completed that goal, now I need to go do this goal.”

But just because these games don’t seem to be as narratively flexible as their pen and paper counterparts doesn’t mean that the notion of “quests” (as a personally significant journey) has no value. On the contrary, I think that if used correctly quests can breathe life into an RPG experience and provide much-needed context and personal stakes.

Quests and Expression

It seems like I’m complaining that “quest” is the wrong word for these activities – that we should just replace “quest” with “task” and call it a day. That’s not right, though.

Are there too many by-the-numbers “kill 10 bogwraiths” tasks in videogames? Yes, it’s a running joke in the industry. But there’s still a time and a place for those tasks: I don’t want to get rid of them entirely, or just rebrand them.

In fact, I believe they can be appropriate. I just finished The Witcher(yes, the original, and yes, I am hilariously behind the times). There’s a fair bit of grind in that game; every location has a billboard full of exactly these “bring me 6 spider eyes” tasks. But it makes sense in context, because Geralt is a witcher and witchers kill monsters, and historically bounties have been offered to curb pest populations. (Eg. European rat catchers who received a reward for each rat tail they presented at the town hall.) A repetitive task is perfect here because it’s his version of the 9-to-5. In fact, it helps to define Geralt’s character since it further reinforces the fact this is Geralt’s day job: without the occasional tedious task we would feel too much like a high-fantasy hero, not the grizzled low-fantasy freelancer trying to do the right thing while also getting paid a fair wage.

Nevertheless, I believe relying on this model too much undermines storytelling, characterisation and player expression. The term “quest” has necessarily become diluted in a genre where “You have completed 38 quests” is commonplace. We pursue quests at a leisurely pace, at our convenience. In many open world games quests become distant goals that linger at the back of our minds – “I guess I’ll find myself in Whiterun again some time, I’ll just do it then” – more like New Year’s resolutions than anything urgent or character-defining. You might as well scavenge that trashcan / loot that endtable: you’ve got time.

Other times quests are more integrated into the roleplaying but get interrupted, like my Knights of the Old Republic example above: the quest itself was well-presented and tied in well with the game’s underlying questions (are you a light or a dark jedi, do you prioritise power over communication) but I ran into bandits and space-wolves a dozen times before I got anywhere near the quest area. These interruptions to the flow of the quest narrative – inserting “filler” tasks and opportunities between the start and end of the quest – not only rob quests of their sense of urgency but also undercut their narrative punch. If meting out justice or overcoming an obstacle is meant to resonate, players should be able to focus on them without distractions.

So, I think videogames can learn something from literary quests. These are personally significant journeys where choice and character are paramount. To put it another way, a (literary) quest is a personally significant journey for a symbolic object standing for certain values, and the obstacles the seeker overcomes (and the way they overcome them) manifests something about their character. A quest is a literary device which helps define a character in relation to an ideal, illustrating their relation to each other through the character’s actions.

A man on a quest. Each time Mulder chooses to throw himself back into it, the quest serves to show us how committed (obsessed?) he is to truth, faith and holding the powerful accountable.

To me this is a good fit for CRPGs. These games want players to inhabit other bodies and personalities (to roleplay) and to allow storytelling to emerge from that, but they struggle because the complexities of non-digital stories and characters can never be matched by the algorithms which run the game. (There are games that try – Crusader Kings 2 comes to mind, though it’s not an RPG – but note that real history is so, so much more complex than anything CK2 can come up with.) The go-to solution is to produce aton of content, but the prevalence of filler tasks shows, I think, that this doesn’t correlate with better or better-framed experiences. But by giving players quests to pursue, game designers can allow players to define their characters in relation to whatever the quest is about in an intuitive way.

By giving the player an investigation quest, for example (maybe they have to interrogate witnesses and suspects to solve a crime) developers would ask players, “How do you want your character to be defined in terms of their pursuit of truth and justice?” In other words, are they a good cop? A bad cop? Do they dig for the truth even if it could destroy them, or do they think ignorance is bliss some of the time? Players can then decide how their character responds to various challenges and obstacles during the quest, allowing them to express how they feel their character should be defined in terms of these values. What’s helpful about this model is that it provides a framework which players can use (and implicitly understand) to help them roleplay, and make their characters feel more their own: they become characters with internal lives and values, rather than puppets to steer through consecutive to-do lists.

Time for some examples

Image from http://www.desktopwallpapers4.me/games/mass-effect-2-18026/

The example that jumps out at me is the crew member missions for Mass Effect 2, which were praised by critics. In ME2 each crew member has a backstory which will eventually bloom into a fully-fledged mission. A crew member with a difficult father-daughter relationship might suddenly have to rescue her father, for example; a crew member with a shady past might take care of some unfinished business. The player character tags along and helps the crew member complete the mission.

What’s immediately obvious is that these are not by-the-numbers missions. These crew members have hinted at their backstories before you even realise there is a mission attached, so all of the character arcs climax and resolve in a way that feels natural and earned. (That’s not to say they resolve well for the player, of course: make the wrong choice and a mission could end badly for that character.) The stakes are not just “If I go on this mission maybe this character will like me more”, though that’s a part of it. The stakes are defeating the demons which have plagued your friends, putting their fears to rest, or helping them overcome something together they may not be able to defeat alone.

Each contain choices, as well: after all, this is Mass Effect. You could choose to disrespect the wishes of a crew member, to act aggressively, to try and reason with people, to compromise. It’s not like these dialogue choices aren’t present elsewhere – the “build bridges/burn bridges” dialogue dichotomy is a big draw of the series – but it seems more forceful here, because the stakes are higher. Elsewhere, you can punch a reporter and the results might be negligible. Here, if you act in the wrong way it can have disastrous repercussions. Again, this is a quest in the literary sense: everything you do in this mission takes on heightened meaning, and will define your character going forward.

A minor point: while the foregrounding for these missions goes back several play-hours (the crew members drop hints about their past all the time), the missions themselves are short and uninterrupted so the player can focus on them completely. Throughout each of these missions you wonder how to feel about each of the actors, who’s in the right, whether there’s an angle you hadn’t considered and, ultimately, how to judge everyone. That simply wouldn’t work if it were broken up. It allows the missions to be the rich, expressive spaces they were designed to be.

Image from http://megagames.com/fixes/planescape-torment

Another example of a game with meaningful quests is the much-praised Planescape: Torment. This game, building on the Baldur’s Gate formula, has the quest system we recognise from CRPGs, but the main quest is a quest in every sense. The player character, we discover, is an immortal who sometimes loses his memory when he “dies”; as such, he has lived an unknown number of past “lives”, each one ended by a sudden bout of amnesia brought on by the trauma of death. Some of these past incarnations, we discover, were kind; others were brutal. The player begins a quest to discover who they are, how they became this way and why this all happened, and on the way discovers what remains of their past incarnations; the game’s tagline and central question is “What can change the nature of a man?”

This harmonises with the conventions of the CRPG genre, since most RPGs ask the question “Who are you?”, and let the player’s choices and actions determine the answer. This is especially complicated and juicy in a game where “Who are you?” can also be read as “Who were you? Are you the same person as your past selves? Is it even possible for a person to change?” This quest is not as tightly designed as ME2‘s crew missions – it lasts at least 30 hours, not 30 minutes – but it is a game-long quest which really is a quest in the traditional sense. It’s ultimately about the most fundamental aspects of the protagonist’s identity. As such, the main quest enriches and adds context to all of the minor choices and character-driven moments in the game. The player is playing a game about a man seeking his identity while asking questions about the nature of identity, and play is accomplished by defining this character’s identity through choice and action while also thinking about those same questions of identity. It’s an unusually thoughtful discussion of roleplaying since one could argue the protagonist achieves personhood after his amnesia by roleplaying the person he wants to become: the questions “Who should I be? How do I get there?” are implicitly asked by both player and character, even if the protagonist never asks them aloud.

Questing onward

My best videogame memories are not scripted sequences but moments where my choices (and failings) had a profound impact on my character and their world. In ME2, for example, I ignored the wishes of a friend during her crew mission because I thought I knew her mind better than she did. The result? She never talked to me again and, when it came to the final mission of the game, was killed. In the sequel I realised with horror that I needed her to broker a peace between two races. Since she was dead, they fought and one race was completely wiped out. My character’s arrogance – myarrogance – was responsible for her death and the death of her people.

This story isn’t great fiction, and it’s not unique. But my choices and those of my character showed me where she stood: how much she respected her crew, how much she feared losing them, and how much that fear cost her. My Commander Shepard is a fixture in my memory, and not just another forgettable protagonist, because she and I made choices and mistakes in difficult, risky situations. Situations which were, of course, carefully designed to elicit those reactions, or something like them.