RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Warren Spector on Ultima, Origin, and CRPG Design

RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Warren Spector on Ultima, Origin, and CRPG Design

Codex Interview - posted by Crooked Bee on Tue 22 October 2013, 16:18:33

Tags: Origin Systems; Retrospective Interview; Ultima Underworld; Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds; Ultima VI: The False Prophet; Ultima VII: Serpent Isle; Ultima VIII: Pagan; Warren Spector; Worlds of Ultima: Martian Dreams; Worlds of Ultima: The Savage EmpireWarren Spector is one of the most celebrated names in the video game industry, most famous for his involvement with Looking Glass Studios' System Shock and Ion Storm's Deus Ex, as well as his philosophy of game design that emphasizes player choice, simulation, and interactive storytelling. At the end of the 1980s - beginning of the 1990s, however, before he came to work on his most widely known titles, Warren also did important work at Richard Garriott's Origin Systems, having been instrumental in the design and production of such unique and significant computer role-playing games as Ultima VI, Ultima VII Part 2: Serpent Isle, the Worlds of Ultima spin-offs (Savage Empire and Martian Dreams), and Ultima Underworld I & II (developed under Origin's supervision by Blue Sky Productions which later became Looking Glass), not to mention his role on various other Origin games such as Wing Commander, Bad Blood or Crusader: No Remorse.

As far as we know, it's been many years since anyone interviewed Warren Spector at length about his work on the Ultima games; this interview aims to rectify that. In it, Warren talks about his pen-and-paper background, his time at Origin and the design philosophy behind the games he was involved with at the time, and also shares some thoughts on the history of the CRPG genre. Have a snippet:

Read the full interview: RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Warren Spector on Ultima, Origin, and CRPG Design

As far as we know, it's been many years since anyone interviewed Warren Spector at length about his work on the Ultima games; this interview aims to rectify that. In it, Warren talks about his pen-and-paper background, his time at Origin and the design philosophy behind the games he was involved with at the time, and also shares some thoughts on the history of the CRPG genre. Have a snippet:

Could you tell us how the Worlds of Ultima series originated and why Origin decided to take the approach of making these games deliberately weird? Who was responsible for that, and to what extent were you involved in the series’ creation and the direction it was taking? As an aside, what exactly was your own role on Savage Empire, since you don’t actually appear in the credits despite being a character in the game?

You know, I bet everyone involved in the creation of the Worlds of Ultima series has a different view of how that sub-series came to be. My memory is probably as inaccurate as anyone's, but I remember it being my idea, to be honest. We simply needed to create more games than Richard Garriott and Chris Roberts could produce. And with guys like Paul Neurath and Greg Malone and Stuart Marks and Todd Porter gone, guys like Jeff Johannigman and I had to step up. I think I was the one to suggest creating a spin-off series of non-numbered Ultimas, produced by me and Jeff, that would re-use tech from last numbered one while Richard was creating ground-up new tech for the next numbered one.

My role on Savage Empire started and ended early. I wrote up the initial 20-ish page design spec (which I wish I still had!) for a lost world, dinosaur game. And I wrote up a spec for what became Martian Dreams. I couldn't make both and wasn't willing to pass up the chance to make a Victorian time travel game, so I took on Martian Dreams and Johan did Savage Empire. He and designer, Aaron Allston, probably scrapped my initial design doc instantly. No matter, Savage Empire ended up being a swell game and, despite all the traipsing around the Martian surface, I'm still inordinately proud of Martian Dreams. Frankly, I wish we'd kept the Worlds of Ultima games going.

Starting from Ultima IV, each game in the series improved upon its predecessor, until we arrive at Ultima VIII: Pagan – a run 'n jump game focused around a lone Avatar and leaving behind the meticulous worldbuilding of the previous Ultima games. So, what was going on with Ultima VIII? The way you see and remember it, what made Origin decide to abandon its strategy of gradual iteration on the classic Ultima formula? Was there perhaps at one point a different vision for the game?

To be frank, I was working on other things when U8 was in development so you'd probably want to ask someone else what was going on with that team and that project. As an observer at Origin but outside the team, my impression at the time was that the Ultima guys had a bit of "Commander envy" – as in Wing Commander and Strike Commander envy. Chris's games had managed to reach a broader audience than anything Origin had done to date and I think U8 was an attempt to go after a broader audience. I did the same thing years later between Deus Ex and Deus Ex: Invisible War. The obvious way to reach a broad audience is to simplify, streamline and up the action. That doesn't have to compromise the integrity of your concept but it can and often does. Maybe that's what was going on in U8. But, again, that's a lot of speculation on my part.

As far as connections between Serpent Isle and U8 go, there really weren't many – if any. My teams and Richard's teams worked largely independently. Maybe too much so… We all tried to be aware of what was going on, Ultima-wise, on "the other side" but we were so heads-down, working like crazed weasels to hit our dates, we didn't coordinate as much as we could have. Nothing as dramatic as a shifting product vision, I'm afraid!

Serpent Isle was your last "old school" party-based RPG. In the late 90s, while at Looking Glass, you developed a design philosophy emphasizing player choice, and then you continued with that approach in Deus Ex. During the same period, however, Black Isle Studios was developing its own signature gameplay style which also emphasized player choice, albeit in a different way – games like Tim Cain’s Fallout or Chris Avellone’s Planescape: Torment were traditional party-based CRPGs with an isometric perspective, deep dialogue trees, etc. One could imagine that, had you continued making games like Serpent Isle, they would have turned out a lot like those titles. Do you ever regret not having been able to pursue that path? Do you think you could have married the form of Serpent Isle with the essence of Deus Ex, so to speak?

Interesting question… I think I could have married Serpent Isle's party basis with DX, but I wouldn't have done it with dialogue trees and traditional RPG tropes. The key thing about games like Underworld and System Shock and Deus Ex and, yes, even Disney Epic Mickey, is that they don't rely as much on scripting (dialogue or interaction scripting), as on simulation. I think it'd be possible to make an isometric, party-based game that offers all the player choice and consequence stuff, for sure. I've often thought about giving that a try. You never know – it just might happen some day!

The interesting thing to me, though, is that you really see a radical difference between the philosophy underlying Serpent Isle and the DX philosophy. I see them both as being on the same evolutionary path. I mean, the whole choice and consequence thing grew out of a design philosophy I was steeped in during my tabletop days and then reinforced by Richard's approach in Ultima VI – the "two solutions to every puzzle" idea. The moment that changed my design life was watching a guy play Ultima VI and solve a puzzle in a way Richard and I never thought of. I kind of decided then and there to make nothing but games designed to empower players. I always thought Serpent Isle was one of those games! Maybe I'm wrong!

You know, I bet everyone involved in the creation of the Worlds of Ultima series has a different view of how that sub-series came to be. My memory is probably as inaccurate as anyone's, but I remember it being my idea, to be honest. We simply needed to create more games than Richard Garriott and Chris Roberts could produce. And with guys like Paul Neurath and Greg Malone and Stuart Marks and Todd Porter gone, guys like Jeff Johannigman and I had to step up. I think I was the one to suggest creating a spin-off series of non-numbered Ultimas, produced by me and Jeff, that would re-use tech from last numbered one while Richard was creating ground-up new tech for the next numbered one.

My role on Savage Empire started and ended early. I wrote up the initial 20-ish page design spec (which I wish I still had!) for a lost world, dinosaur game. And I wrote up a spec for what became Martian Dreams. I couldn't make both and wasn't willing to pass up the chance to make a Victorian time travel game, so I took on Martian Dreams and Johan did Savage Empire. He and designer, Aaron Allston, probably scrapped my initial design doc instantly. No matter, Savage Empire ended up being a swell game and, despite all the traipsing around the Martian surface, I'm still inordinately proud of Martian Dreams. Frankly, I wish we'd kept the Worlds of Ultima games going.

Starting from Ultima IV, each game in the series improved upon its predecessor, until we arrive at Ultima VIII: Pagan – a run 'n jump game focused around a lone Avatar and leaving behind the meticulous worldbuilding of the previous Ultima games. So, what was going on with Ultima VIII? The way you see and remember it, what made Origin decide to abandon its strategy of gradual iteration on the classic Ultima formula? Was there perhaps at one point a different vision for the game?

To be frank, I was working on other things when U8 was in development so you'd probably want to ask someone else what was going on with that team and that project. As an observer at Origin but outside the team, my impression at the time was that the Ultima guys had a bit of "Commander envy" – as in Wing Commander and Strike Commander envy. Chris's games had managed to reach a broader audience than anything Origin had done to date and I think U8 was an attempt to go after a broader audience. I did the same thing years later between Deus Ex and Deus Ex: Invisible War. The obvious way to reach a broad audience is to simplify, streamline and up the action. That doesn't have to compromise the integrity of your concept but it can and often does. Maybe that's what was going on in U8. But, again, that's a lot of speculation on my part.

As far as connections between Serpent Isle and U8 go, there really weren't many – if any. My teams and Richard's teams worked largely independently. Maybe too much so… We all tried to be aware of what was going on, Ultima-wise, on "the other side" but we were so heads-down, working like crazed weasels to hit our dates, we didn't coordinate as much as we could have. Nothing as dramatic as a shifting product vision, I'm afraid!

Serpent Isle was your last "old school" party-based RPG. In the late 90s, while at Looking Glass, you developed a design philosophy emphasizing player choice, and then you continued with that approach in Deus Ex. During the same period, however, Black Isle Studios was developing its own signature gameplay style which also emphasized player choice, albeit in a different way – games like Tim Cain’s Fallout or Chris Avellone’s Planescape: Torment were traditional party-based CRPGs with an isometric perspective, deep dialogue trees, etc. One could imagine that, had you continued making games like Serpent Isle, they would have turned out a lot like those titles. Do you ever regret not having been able to pursue that path? Do you think you could have married the form of Serpent Isle with the essence of Deus Ex, so to speak?

Interesting question… I think I could have married Serpent Isle's party basis with DX, but I wouldn't have done it with dialogue trees and traditional RPG tropes. The key thing about games like Underworld and System Shock and Deus Ex and, yes, even Disney Epic Mickey, is that they don't rely as much on scripting (dialogue or interaction scripting), as on simulation. I think it'd be possible to make an isometric, party-based game that offers all the player choice and consequence stuff, for sure. I've often thought about giving that a try. You never know – it just might happen some day!

The interesting thing to me, though, is that you really see a radical difference between the philosophy underlying Serpent Isle and the DX philosophy. I see them both as being on the same evolutionary path. I mean, the whole choice and consequence thing grew out of a design philosophy I was steeped in during my tabletop days and then reinforced by Richard's approach in Ultima VI – the "two solutions to every puzzle" idea. The moment that changed my design life was watching a guy play Ultima VI and solve a puzzle in a way Richard and I never thought of. I kind of decided then and there to make nothing but games designed to empower players. I always thought Serpent Isle was one of those games! Maybe I'm wrong!

Read the full interview: RPG Codex Retrospective Interview: Warren Spector on Ultima, Origin, and CRPG Design

[Interview by Infinitron & Crooked Bee]

Warren Spector is one of the most celebrated names in the video game industry, most famous for his involvement with Looking Glass Studios' System Shock and Ion Storm's Deus Ex, as well as his philosophy of game design that emphasizes player choice, simulation, and interactive storytelling. At the end of the 1980s - beginning of the 1990s, however, before he came to work on his most widely known titles, Warren also did important work at Richard Garriott's Origin Systems, having been instrumental in the design and production of such unique and significant computer role-playing games as Ultima VI, Ultima VII Part 2: Serpent Isle, the Worlds of Ultima spin-offs (Savage Empire and Martian Dreams), and Ultima Underworld I & II (developed under Origin's supervision by Blue Sky Productions which later became Looking Glass), not to mention his role on various other Origin games such as Wing Commander, Bad Blood or Crusader: No Remorse.

As far as we know, it's been many years since anyone interviewed Warren Spector at length about his work on the Ultima games; this interview aims to rectify that. In it, Warren talks about his pen-and-paper background, his time at Origin and the design philosophy behind the games he was involved with at the time, and also shares some thoughts on the history of the CRPG genre.

RPG Codex: Looking back at your career, one can observe two Warren Spectors – the early 90s storyteller Spector of Origin, who took the setting created by Richard Garriott and helped flesh it out with detail and amazing stories, and the late 90s designer Spector of Looking Glass and Ion Storm, famous for a philosophy of game design emphasizing player choice and immersive simulation. That's an interesting transformation because if we look at Martian Dreams or Serpent Isle, those games were actually more linear and "railroaded" than Ultima VI or VII (developed under Garriott's supervision) and more focused on storytelling at the expense of some of the player freedom characteristic of the mainline Ultimas. How do you explain this shift?

Before coming to Origin, you had spent six years at Steven Jackson Games and TSR. How, and to what extent, was your approach to storytelling and video game design while at Origin influenced by your work at SJG and TSR and your pen-and-paper experience? What would you say were the main things you had learned during that period -- and how did they carry over to your later career?

You have a producer and a designer credit for Ultima VI: The False Prophet, but unlike most of the other roleplaying games you've worked on, Ultima VI doesn't come across as particularly "Spectorian". Can you tell us a bit about your role in its development? Similarly, could you tell us more about your involvement with Wing Commander (1990), Bad Blood (1990), and Crusader: No Remorse (1995)?

Map of Serpent Isle

From what we know, Serpent Isle was originally conceived by Jeff George as a pirate-themed game that wasn't supposed to be a part of the core Ultima series. Do you recall anything about George’s original design? How challenging was it for you to take over the project after George had left the company, and what influence did you have on turning the game into a more traditional Ultima title?

Serpent Isle’s recurring themes were those of religious conflict, dissidence and colonization. First inhabited by an ancient people with a sophisticated culture who destroyed each other in a massive religious war, the land was ages later settled by the New Sosarians fleeing the "tyranny" of Lord British. Centuries after that, the villain Batlin arrived with a crew of Fellowship members – most of them innocents, who could ironically be seen as another people persecuted by Lord British. And then came the Avatar, hunting them down and encountering the societies built by those who had rejected the Britannian ways. So you had these multiple layers of religious conflict, of dissidents fleeing persecution and colonizing new worlds. It was, in short, a thoroughly inspired game – a love letter to the fans who took the Ultima lore seriously. However, we've never seen any member of the Serpent Isle team speak at length about the ideas and inspirations behind it – a real shame, because a lot of thought went into its creation. So we'd be very pleased if you could shed some light on this topic. How did the world and history of Serpent Isle come together the way they did?

Could you tell us how the Worlds of Ultima series originated and why Origin decided to take the approach of making these games deliberately weird? Who was responsible for that, and to what extent were you involved in the series’ creation and the direction it was taking? As an aside, what exactly was your own role on Savage Empire, since you don’t actually appear in the credits despite being a character in the game?

Dr. Spector in Worlds of Ultima: Martian Dreams

Savage Empire and Martian Dreams were both homages to early 20th century "pulp". Were any further Worlds of Ultima supposed to continue on that theme? In general, what were some of the ideas that were being kicked around before the Worlds of Ultima series got discontinued?

The Ultima spin-offs were all connected to some extent with the storyline of the main series. Ultima Underworld 2 served as a direct sequel to Ultima VII, expanding the backstory of the Guardian and fleshing out the personalities of the Avatar's friends and companions. Serpent Isle had references going all the way back to Ultima III, and even Savage Empire and Martian Dreams had direct nods to the main series – the Xorinite Wisp from Ultima VI in Savage Empire and the Shadowlords from Ultima V in Martian Dreams. Overall, it seems like the Ultima setting was being built up as a richer, more coherent mythos during that time and was becoming a fully-fledged "campaign setting", striving to stand alongside the likes of the Forgotten Realms and Middle Earth. Who was responsible for that? And why did it suddenly stop and regress after Serpent Isle?

In light of the previous question, we’d like to know more about the writing teams for the Ultima series during the early 90s. There was a rapid improvement in quality there, starting with the rather rudimentary and uneven writing of Ultima VI (1990) and ending up with some of the best writing ever seen in the genre in Ultima VII (1992) and Serpent Isle (1993). The characters became more fleshed out and realistic, the storytelling was better paced, and overall the writing just got better, in terms of theme and stylistic consistency – all in just a few years. Can you tell us more about this "professionalization" of Origin's writing talent? Who was behind it? Did you contribute to it, personally?

It's said that Richard Garriott had a rule that no two Ultimas must share the same code, but the spin-offs seem to have been exempt from that rule. Savage Empire and Martian Dreams were based on the Ultima VI engine, and Serpent Isle (and also Arthurian Legends, had it been released) was based on the Ultima VII engine. Reusing a game engine gives developers a chance to iterate and improve it, and add new features. When you developed the spinoffs, were you looking to improve on any perceived weaknesses in Ultima VI and Ultima VII?

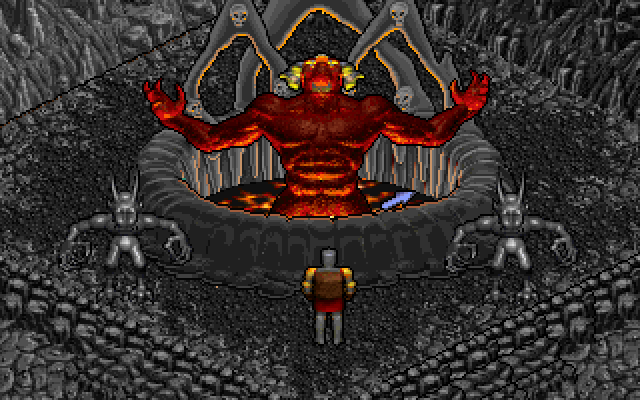

Ultima 8: Pagan broke with the previous Ultima games by being focused around a lone Avatar

Starting from Ultima IV, each game in the series improved upon its predecessor. Ultima V added day-night cycles and NPC schedules, Ultima VI implemented a seamless interactive world, and Ultima VII made it even richer, with a greatly improved quality of writing. And then we arrive at Ultima VIII: Pagan. In interviews, Richard Garriott has said that he wasn't given enough time to finish the game properly, and yet it seems that even if he had, U8 would still have been a very different beast – a run 'n jump game focused around a lone Avatar and leaving behind the meticulous worldbuilding of the previous Ultima games. So, what was going on with Ultima VIII? The way you see and remember it, what made Origin decide to abandon its strategy of gradual iteration on the classic Ultima formula? Serpent Isle had a character from the world of Pagan - Morghrim the Forest Master, but there seems to be no connection between him and the actual U8. Was there perhaps at one point a different vision for the game?

Serpent Isle was your last "old school" party-based RPG. In the late 90s, while at Looking Glass, you developed a design philosophy emphasizing player choice, and then you continued with that approach in Deus Ex. During the same period, however, Black Isle Studios was developing its own signature gameplay style which also emphasized player choice, albeit in a different way – games like Tim Cain’s Fallout or Chris Avellone’s Planescape: Torment were traditional party-based CRPGs with an isometric perspective, deep dialogue trees, etc. One could imagine that, had you continued making games like Serpent Isle, they would have turned out a lot like those titles. Do you ever regret not having been able to pursue that path? Do you think you could have married the form of Serpent Isle with the essence of Deus Ex, so to speak?

At one point, Origin's RPGs seemed to be divided in two separate lineages. There were the Garriott games, the mainline Ultimas that tended to have a more "sandbox" structure. And there were the Spector games, more scripted and story-oriented. Interestingly, although the RPG genre would eventually progress towards more story-centric and scripted experiences (see any contemporary game by BioWare, Obsidian Entertainment, or CD Projekt RED), your RPGs never really achieved the same commercial success that Garriott's did. In retrospect, it seems like Origin missed out in a big way on an important industry trend. Do you think your games could have done better than they did?

Some ex-Origin people (Denis Loubet, Harvey Smith, Sheri Graner Ray) have shared their negative opinion on the "later Origin", when it grew large and non-transparent. As Denis Loubet put it, "You could no longer know everything that was going on because everyone was in one tight clique or another and jealously guarded their turf." "Nobody was thinking about the gamers' experience", Harvey Smith once described it. Do you share that kind of sentiment about the decline of Origin Systems in its later years, even before the EA buyout?

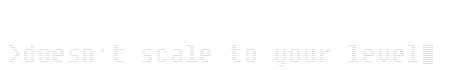

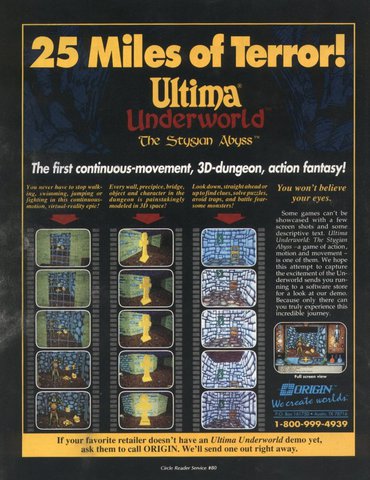

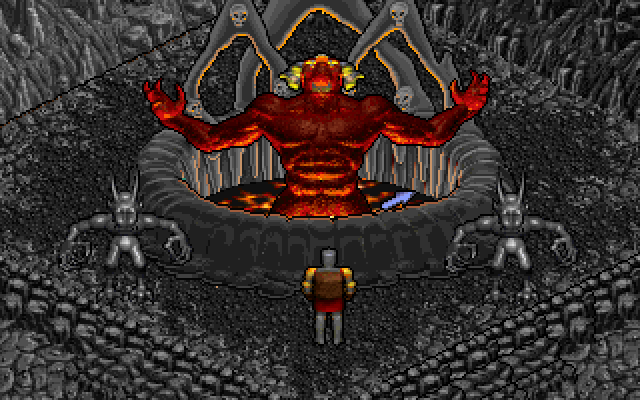

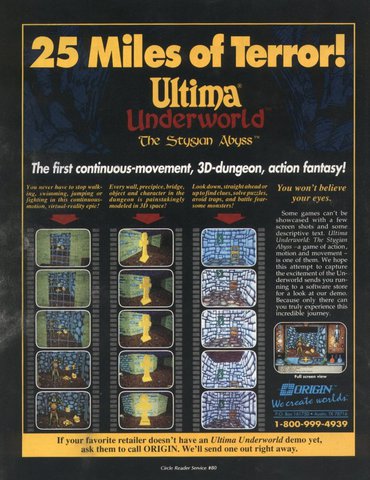

Ultima Underworld: the first "continuous-movement" first person 3D RPG

The story of the first Ultima Underworld was pretty minimalistic, and only tangentially related to the plot of the main Ultima series. Ultima Underworld 2, on the other hand, was a direct sequel to Ultima VII. It featured many characters from that game - not just the major characters that had recurred throughout the entire series, but also minor ones like Lord British's servants and staff, fleshed out with additional characterization. In general, comparing Underworld 1 with Underworld 2 is a lot like comparing Ultima 7 and Serpent Isle, in that the latter has a much greater emphasis on story. What made you decide to take that approach? Would it be correct to assume that you were more involved with the development of Underworld 2 than you were with Underworld 1?

In a recent interview, Paul Neurath said that Ultima Underworld 2 was a rushed product with "cut corners". That is a bit surprising, since despite having perhaps slightly less gigantic dungeon maps to explore, Underworld 2 was a rich and expansive game which didn't feel incomplete at all. Can you tell us more about that? Were there any plans for additional content in Underworld 2 that didn't make it in due to a lack of time?

Chroniclers of the history of computer roleplaying games sometimes speak of a period in the mid-1990s when the genre suffered a decline – critically, commercially, and in terms of the sheer numbers of games released. See for instance this article by Rowan Kaiser, or Wikipedia. It's probably not a coincidence that it was around that same time that you moved from Origin to Looking Glass, the latter having been focused on a genre of games that investors and publishers considered more "contemporary". As somebody who was very much at the heart of the industry during that time, can you tell us more about these events? After a Golden Age spanning from the 1980s all the way up to around 1993, how could an entire genre collapse so suddenly, across so many different companies?

We are grateful to Warren Spector for taking his time to answer our questions.

Warren Spector is one of the most celebrated names in the video game industry, most famous for his involvement with Looking Glass Studios' System Shock and Ion Storm's Deus Ex, as well as his philosophy of game design that emphasizes player choice, simulation, and interactive storytelling. At the end of the 1980s - beginning of the 1990s, however, before he came to work on his most widely known titles, Warren also did important work at Richard Garriott's Origin Systems, having been instrumental in the design and production of such unique and significant computer role-playing games as Ultima VI, Ultima VII Part 2: Serpent Isle, the Worlds of Ultima spin-offs (Savage Empire and Martian Dreams), and Ultima Underworld I & II (developed under Origin's supervision by Blue Sky Productions which later became Looking Glass), not to mention his role on various other Origin games such as Wing Commander, Bad Blood or Crusader: No Remorse.

As far as we know, it's been many years since anyone interviewed Warren Spector at length about his work on the Ultima games; this interview aims to rectify that. In it, Warren talks about his pen-and-paper background, his time at Origin and the design philosophy behind the games he was involved with at the time, and also shares some thoughts on the history of the CRPG genre.

RPG Codex: Looking back at your career, one can observe two Warren Spectors – the early 90s storyteller Spector of Origin, who took the setting created by Richard Garriott and helped flesh it out with detail and amazing stories, and the late 90s designer Spector of Looking Glass and Ion Storm, famous for a philosophy of game design emphasizing player choice and immersive simulation. That's an interesting transformation because if we look at Martian Dreams or Serpent Isle, those games were actually more linear and "railroaded" than Ultima VI or VII (developed under Garriott's supervision) and more focused on storytelling at the expense of some of the player freedom characteristic of the mainline Ultimas. How do you explain this shift?

Warren Spector: Interestingly, I've never really seen that much of a shift. I've always been interested in interactive storytelling of a sort – but a very specific sort. I'm not much interested in branching tree storylines, where players get to decide only what branch of a tree they choose to follow. I've always been more interested in offering players a single path through a game but giving them a variety of tools with which they can solve problems along that path. So the high level story arc belongs to me and the team – and players can't affect it – while the minute to minute of the story belongs to each player and they have total control over it. I thought that's what my teams and I were doing in Martian Dreams and Serpent Isle, as much as in Deus Ex and other later games. If that isn't the case, or isn't apparent, I guess we didn't do such a good job, did we?...

Before coming to Origin, you had spent six years at Steven Jackson Games and TSR. How, and to what extent, was your approach to storytelling and video game design while at Origin influenced by your work at SJG and TSR and your pen-and-paper experience? What would you say were the main things you had learned during that period -- and how did they carry over to your later career?

I'd say my papergame experience informs everything I do in the electronic games space. I mean, in one sense, my entire career has been an attempt to recapture the feeling – the joy – I experienced telling stories with my friends as we played D&D and The Fantasy Trip and Runequest and the like. Shared authorship is what gaming is all about for me – me and friends rolling D20s, telling our heroes' stories… me and a player at home telling the story of JC Denton together… It's all the same to me or, at least, I'm always trying to make it the same thing.

Having said that, I had to unlearn an awful lot of what I knew as a tabletop game designer when I moved over to Origin. I mean, in tabletop gaming your simulation tools are seriously limited. All you have are dice and combat or spell tables to tell you whether you accomplished something. Even in the early days of electronic games, we could actually simulate action and it always amazed me that developers – to this day – stick with the conventions of tabletop gaming even though they're completely unnecessary in videogames. I mean, who needs levels and combat skills and +5 swords and secret dierolls under the hood when you can simulate the force with which a sword smashes into a wooden door?...

Having said that, I had to unlearn an awful lot of what I knew as a tabletop game designer when I moved over to Origin. I mean, in tabletop gaming your simulation tools are seriously limited. All you have are dice and combat or spell tables to tell you whether you accomplished something. Even in the early days of electronic games, we could actually simulate action and it always amazed me that developers – to this day – stick with the conventions of tabletop gaming even though they're completely unnecessary in videogames. I mean, who needs levels and combat skills and +5 swords and secret dierolls under the hood when you can simulate the force with which a sword smashes into a wooden door?...

You have a producer and a designer credit for Ultima VI: The False Prophet, but unlike most of the other roleplaying games you've worked on, Ultima VI doesn't come across as particularly "Spectorian". Can you tell us a bit about your role in its development? Similarly, could you tell us more about your involvement with Wing Commander (1990), Bad Blood (1990), and Crusader: No Remorse (1995)?

Ultima VI was the first thing I worked on when I left TSR and went to Origin. My role on that game was kind of split. Early on, I worked with Richard on the plot and quests for the game. He and I spent weeks at his house filling in what he called his "black book," a looseleaf notebook he created for every game he did, featuring every character, every location, every quest. It was his way of organizing the game. It was clearly Richard's book and Richard's game but I think I contributed at least something to nearly every page. After that, I became Richard's producer – managed the team and the schedule, dealt with documentation, that sort of thing. There wasn't much design work after that, but I'm still in there, design-wise, if you scratch beneath the surface of the game.

Wing Commander and Bad Blood were done with Chris Roberts. There, I really was mostly a producer. I mean, Wing Commander was totally Chris's game. TOTALLY. I worked with him on schedules and packaging, managed outsourcing of art, dealt with documentation, argued with him when he wanted to push too far on the design side (winning about 3 out of 10 arguments!). I did design and implement one mission sequence, but that's it, design-wise. Bad Blood was made while Chris was focused on Wing Commander so Jeff George and I were the main guys. He handled most of the creative and I dealt with the production there, too.

Crusader? My role on Crusader was mostly to make sure the game got made. The director on that project, Tony Zurovec, was in my business unit at Origin and he came to me with such a clear vision of the game I HAD to find a way for him to make it. Honestly, I didn't quite get it, but when you see passion like Tony's you get out of the way and let great things happen. I supported Tony in whatever way he needed – production, creative, team management, whatever. But if you want to talk about the game on my resume that doesn't feel like one of my games, Crusader would be it!

Basically, the joy of my career has been that I've gotten to work on the games I've wanted to work on and supported the style of games I wanted to see made, even if I wasn't the driving creative force behind one or the other of them. Ultima VI, I'll still happily take some creative credit. The other games you mention, my creative role wasn't as pronounced.

Wing Commander and Bad Blood were done with Chris Roberts. There, I really was mostly a producer. I mean, Wing Commander was totally Chris's game. TOTALLY. I worked with him on schedules and packaging, managed outsourcing of art, dealt with documentation, argued with him when he wanted to push too far on the design side (winning about 3 out of 10 arguments!). I did design and implement one mission sequence, but that's it, design-wise. Bad Blood was made while Chris was focused on Wing Commander so Jeff George and I were the main guys. He handled most of the creative and I dealt with the production there, too.

Crusader? My role on Crusader was mostly to make sure the game got made. The director on that project, Tony Zurovec, was in my business unit at Origin and he came to me with such a clear vision of the game I HAD to find a way for him to make it. Honestly, I didn't quite get it, but when you see passion like Tony's you get out of the way and let great things happen. I supported Tony in whatever way he needed – production, creative, team management, whatever. But if you want to talk about the game on my resume that doesn't feel like one of my games, Crusader would be it!

Basically, the joy of my career has been that I've gotten to work on the games I've wanted to work on and supported the style of games I wanted to see made, even if I wasn't the driving creative force behind one or the other of them. Ultima VI, I'll still happily take some creative credit. The other games you mention, my creative role wasn't as pronounced.

Map of Serpent Isle

From what we know, Serpent Isle was originally conceived by Jeff George as a pirate-themed game that wasn't supposed to be a part of the core Ultima series. Do you recall anything about George’s original design? How challenging was it for you to take over the project after George had left the company, and what influence did you have on turning the game into a more traditional Ultima title?

If memory serves, Serpent Isle was always meant to be an Ultima universe game, but it was a pirate adventure at first. Honestly, it wasn't really making the kind of progress, creatively, I hoped it would – who wouldn't want to play a pirate RPG, right? But when Jeff left, I started working with a fellow named Bill Armintrout on the creative and it became a direct sequel to Ultima VII. The game was made entirely in my unit, so I had a lot to say about the decision and the way the creative [process] unfolded! I don't recall the transition being terribly difficult but that project was by far the biggest I'd worked on at that time and the team grew along with the game's scope. None of us had a clue how to manage a team that size which led to the worst crunch mode I've personally experienced, to this day. That team worked incredibly hard… At the end of the day, the game ran over 100 hours for most players. It even took QA nearly a full 24-hour day to play through. We actually didn't get our first cheat-free playthrough until the day before we signed off and all of us were terrified we might be shipping the buggiest game of our career. Didn't turn out that way, luckily!

Serpent Isle’s recurring themes were those of religious conflict, dissidence and colonization. First inhabited by an ancient people with a sophisticated culture who destroyed each other in a massive religious war, the land was ages later settled by the New Sosarians fleeing the "tyranny" of Lord British. Centuries after that, the villain Batlin arrived with a crew of Fellowship members – most of them innocents, who could ironically be seen as another people persecuted by Lord British. And then came the Avatar, hunting them down and encountering the societies built by those who had rejected the Britannian ways. So you had these multiple layers of religious conflict, of dissidents fleeing persecution and colonizing new worlds. It was, in short, a thoroughly inspired game – a love letter to the fans who took the Ultima lore seriously. However, we've never seen any member of the Serpent Isle team speak at length about the ideas and inspirations behind it – a real shame, because a lot of thought went into its creation. So we'd be very pleased if you could shed some light on this topic. How did the world and history of Serpent Isle come together the way they did?

A lot of the creative energy in the game has to be attributed to Bill Armintrout. He led the design charge and I was happy to support him in his desire to make a game that takes itself and its subject matter seriously. A lot of it, though, was the quality of the team. So many members of that team went on to do great work. We had some real creative muscle there. A lot of what Bill and I had to do was make sure everyone was pulling in the same direction and not get in people's way!

Could you tell us how the Worlds of Ultima series originated and why Origin decided to take the approach of making these games deliberately weird? Who was responsible for that, and to what extent were you involved in the series’ creation and the direction it was taking? As an aside, what exactly was your own role on Savage Empire, since you don’t actually appear in the credits despite being a character in the game?

You know, I bet everyone involved in the creation of the Worlds of Ultima series has a different view of how that sub-series came to be. My memory is probably as inaccurate as anyone's, but I remember it being my idea, to be honest. We simply needed to create more games than Richard Garriott and Chris Roberts could produce. And with guys like Paul Neurath and Greg Malone and Stuart Marks and Todd Porter gone, guys like Jeff Johannigman and I had to step up. I think I was the one to suggest creating a spin-off series of non-numbered Ultimas, produced by me and Jeff, that would re-use tech from last numbered one while Richard was creating ground-up new tech for the next numbered one.

My role on Savage Empire started and ended early. I wrote up the initial 20-ish page design spec (which I wish I still had!) for a lost world, dinosaur game. And I wrote up a spec for what became Martian Dreams. I couldn't make both and wasn't willing to pass up the chance to make a Victorian time travel game, so I took on Martian Dreams and Johan did Savage Empire. He and designer, Aaron Allston, probably scrapped my initial design doc instantly. No matter, Savage Empire ended up being a swell game and, despite all the traipsing around the Martian surface, I'm still inordinately proud of Martian Dreams. Frankly, I wish we'd kept the Worlds of Ultima games going.

My role on Savage Empire started and ended early. I wrote up the initial 20-ish page design spec (which I wish I still had!) for a lost world, dinosaur game. And I wrote up a spec for what became Martian Dreams. I couldn't make both and wasn't willing to pass up the chance to make a Victorian time travel game, so I took on Martian Dreams and Johan did Savage Empire. He and designer, Aaron Allston, probably scrapped my initial design doc instantly. No matter, Savage Empire ended up being a swell game and, despite all the traipsing around the Martian surface, I'm still inordinately proud of Martian Dreams. Frankly, I wish we'd kept the Worlds of Ultima games going.

Dr. Spector in Worlds of Ultima: Martian Dreams

Savage Empire and Martian Dreams were both homages to early 20th century "pulp". Were any further Worlds of Ultima supposed to continue on that theme? In general, what were some of the ideas that were being kicked around before the Worlds of Ultima series got discontinued?

Honestly, neither Savage Empire nor Martian Dreams sold worth a darn, so there weren't a lot of Worlds of Ultima ideas kicked around once we saw the writing on the wall. I did begin development on a Worlds title, "Arthurian Legend," which was going to be pretty much what it sounds like – a faithful rendition of the traditional Arthurian myths in PC game form. We got reasonable far into preproduction but the Worlds of Ultima sales simply didn't justify continuing.

The Ultima spin-offs were all connected to some extent with the storyline of the main series. Ultima Underworld 2 served as a direct sequel to Ultima VII, expanding the backstory of the Guardian and fleshing out the personalities of the Avatar's friends and companions. Serpent Isle had references going all the way back to Ultima III, and even Savage Empire and Martian Dreams had direct nods to the main series – the Xorinite Wisp from Ultima VI in Savage Empire and the Shadowlords from Ultima V in Martian Dreams. Overall, it seems like the Ultima setting was being built up as a richer, more coherent mythos during that time and was becoming a fully-fledged "campaign setting", striving to stand alongside the likes of the Forgotten Realms and Middle Earth. Who was responsible for that? And why did it suddenly stop and regress after Serpent Isle?

I think you give us more credit than we deserve when you ask who was responsible for the expansion of the Ultima universe. We all just loved that world and wanted to reuse elements from earlier games because it pleased us and we knew it would please the fans. As close as we had to a plan – Richard, me, Johan, Paul Neurath, Doug Church and others – was "wouldn't it be cool if…" And we were all lucky enough to work with Richard, who was open to allowing others to flesh out and enhance the richness of the world he created. But there was no plan, really.

In light of the previous question, we’d like to know more about the writing teams for the Ultima series during the early 90s. There was a rapid improvement in quality there, starting with the rather rudimentary and uneven writing of Ultima VI (1990) and ending up with some of the best writing ever seen in the genre in Ultima VII (1992) and Serpent Isle (1993). The characters became more fleshed out and realistic, the storytelling was better paced, and overall the writing just got better, in terms of theme and stylistic consistency – all in just a few years. Can you tell us more about this "professionalization" of Origin's writing talent? Who was behind it? Did you contribute to it, personally?

I wouldn't want to swear to this, but I'm pretty sure there were no professional writers at Origin before I showed up. (And I was barely a pro, myself! I mean a bunch of game rules and modules, some choose your own adventure stuff and one published novel don't scream "professional game writer!") I'm pretty sure Richard and some of the team members wrote all the dialogue for the Ultimas before VI.

When I started there, teams were just starting to ramp up in size and the games were getting significantly bigger, with the move from Apples to IBM PCs with hard drives as the target platform. It just wasn't possible for team members to wear multiple hats anymore. I think we all saw that. On Ultima VI, we brought on some dedicated writing talent – Steve Beeman (who turned out to be a terrific coder and team lead) and Dr. Cat, a programmer/designer who'd been working with Origin for a while. That was the start of it. Once we got to Ultima VII the scope was so great, we had to expand again and that's when we really started going after professional writers. I interviewed dozens of writers back then, and over a couple of years hired more than 20 for Origin – we hired screenwriters, novelists, comic book writers… When you're making 100 hour games, you need a lot of words! When those 100 hours are largely under player control, you need even more! I'd be surprised if there was another game company that put such a premium on writing back then. You might even have to look to Bioware, many years later, to find a studio that valued writing as highly as we did.

You asked if I did any writing? Some. A lot of documentation work, some in-game stuff, but I had a job of my own. I was a producer. And it was tough for me to wear multiple hats, too. We needed full-time staff writers. So we got them.

When I started there, teams were just starting to ramp up in size and the games were getting significantly bigger, with the move from Apples to IBM PCs with hard drives as the target platform. It just wasn't possible for team members to wear multiple hats anymore. I think we all saw that. On Ultima VI, we brought on some dedicated writing talent – Steve Beeman (who turned out to be a terrific coder and team lead) and Dr. Cat, a programmer/designer who'd been working with Origin for a while. That was the start of it. Once we got to Ultima VII the scope was so great, we had to expand again and that's when we really started going after professional writers. I interviewed dozens of writers back then, and over a couple of years hired more than 20 for Origin – we hired screenwriters, novelists, comic book writers… When you're making 100 hour games, you need a lot of words! When those 100 hours are largely under player control, you need even more! I'd be surprised if there was another game company that put such a premium on writing back then. You might even have to look to Bioware, many years later, to find a studio that valued writing as highly as we did.

You asked if I did any writing? Some. A lot of documentation work, some in-game stuff, but I had a job of my own. I was a producer. And it was tough for me to wear multiple hats, too. We needed full-time staff writers. So we got them.

It's said that Richard Garriott had a rule that no two Ultimas must share the same code, but the spin-offs seem to have been exempt from that rule. Savage Empire and Martian Dreams were based on the Ultima VI engine, and Serpent Isle (and also Arthurian Legends, had it been released) was based on the Ultima VII engine. Reusing a game engine gives developers a chance to iterate and improve it, and add new features. When you developed the spinoffs, were you looking to improve on any perceived weaknesses in Ultima VI and Ultima VII?

You're right about Richard scrapping all the code between numbered Ultimas. Some of us thought that was pretty wasteful and said we could take the old code, use it for spinoffs and new games, while Richard and his core team started building the codebase for the next numbered game.

The idea was to get more games out – high quality games, but relatively quickly and at relatively low cost – so I don't think any of us were looking to improve upon the code particularly. I mean, you always want to improve performance, where you can, but the Ultima spinoffs were content plays, not tech demos. We wanted to clean up UIs, replace as much of the content as we could… improve on the content (which we were able to do because we had a stable code base and could push it further than the guys who had to build the code and the game at the same time).

Nah. I don't think we were trying to improve things much. Just introduce new gameplay elements as necessary and polish, polish, polish.

The idea was to get more games out – high quality games, but relatively quickly and at relatively low cost – so I don't think any of us were looking to improve upon the code particularly. I mean, you always want to improve performance, where you can, but the Ultima spinoffs were content plays, not tech demos. We wanted to clean up UIs, replace as much of the content as we could… improve on the content (which we were able to do because we had a stable code base and could push it further than the guys who had to build the code and the game at the same time).

Nah. I don't think we were trying to improve things much. Just introduce new gameplay elements as necessary and polish, polish, polish.

Ultima 8: Pagan broke with the previous Ultima games by being focused around a lone Avatar

Starting from Ultima IV, each game in the series improved upon its predecessor. Ultima V added day-night cycles and NPC schedules, Ultima VI implemented a seamless interactive world, and Ultima VII made it even richer, with a greatly improved quality of writing. And then we arrive at Ultima VIII: Pagan. In interviews, Richard Garriott has said that he wasn't given enough time to finish the game properly, and yet it seems that even if he had, U8 would still have been a very different beast – a run 'n jump game focused around a lone Avatar and leaving behind the meticulous worldbuilding of the previous Ultima games. So, what was going on with Ultima VIII? The way you see and remember it, what made Origin decide to abandon its strategy of gradual iteration on the classic Ultima formula? Serpent Isle had a character from the world of Pagan - Morghrim the Forest Master, but there seems to be no connection between him and the actual U8. Was there perhaps at one point a different vision for the game?

To be frank, I was working on other things when U8 was in development so you'd probably want to ask someone else what was going on with that team and that project. As an observer at Origin but outside the team, my impression at the time was that the Ultima guys had a bit of "Commander envy" – as in Wing Commander and Strike Commander envy. Chris's games had managed to reach a broader audience than anything Origin had done to date and I think U8 was an attempt to go after a broader audience. I did the same thing years later between Deus Ex and Deus Ex: Invisible War. The obvious way to reach a broad audience is to simplify, streamline and up the action. That doesn't have to compromise the integrity of your concept but it can and often does. Maybe that's what was going on in U8. But, again, that's a lot of speculation on my part.

As far as connections between Serpent Isle and U8 go, there really weren't many – if any. My teams and Richard's teams worked largely independently. Maybe too much so… We all tried to be aware of what was going on, Ultima-wise, on "the other side" but we were so heads-down, working like crazed weasels to hit our dates, we didn't coordinate as much as we could have. Nothing as dramatic as a shifting product vision, I'm afraid!

As far as connections between Serpent Isle and U8 go, there really weren't many – if any. My teams and Richard's teams worked largely independently. Maybe too much so… We all tried to be aware of what was going on, Ultima-wise, on "the other side" but we were so heads-down, working like crazed weasels to hit our dates, we didn't coordinate as much as we could have. Nothing as dramatic as a shifting product vision, I'm afraid!

Serpent Isle was your last "old school" party-based RPG. In the late 90s, while at Looking Glass, you developed a design philosophy emphasizing player choice, and then you continued with that approach in Deus Ex. During the same period, however, Black Isle Studios was developing its own signature gameplay style which also emphasized player choice, albeit in a different way – games like Tim Cain’s Fallout or Chris Avellone’s Planescape: Torment were traditional party-based CRPGs with an isometric perspective, deep dialogue trees, etc. One could imagine that, had you continued making games like Serpent Isle, they would have turned out a lot like those titles. Do you ever regret not having been able to pursue that path? Do you think you could have married the form of Serpent Isle with the essence of Deus Ex, so to speak?

Interesting question… I think I could have married Serpent Isle's party basis with DX, but I wouldn't have done it with dialogue trees and traditional RPG tropes. The key thing about games like Underworld and System Shock and Deus Ex and, yes, even Disney Epic Mickey, is that they don't rely as much on scripting (dialogue or interaction scripting), as on simulation. I think it'd be possible to make an isometric, party-based game that offers all the player choice and consequence stuff, for sure. I've often thought about giving that a try. You never know – it just might happen some day!

The interesting thing to me, though, is that you really see a radical difference between the philosophy underlying Serpent Isle and the DX philosophy. I see them both as being on the same evolutionary path. I mean, the whole choice and consequence thing grew out of a design philosophy I was steeped in during my tabletop days and then reinforced by Richard's approach in Ultima VI – the "two solutions to every puzzle" idea. The moment that changed my design life was watching a guy play Ultima VI and solve a puzzle in a way Richard and I never thought of. I kind of decided then and there to make nothing but games designed to empower players. I always thought Serpent Isle was one of those games! Maybe I'm wrong!

The interesting thing to me, though, is that you really see a radical difference between the philosophy underlying Serpent Isle and the DX philosophy. I see them both as being on the same evolutionary path. I mean, the whole choice and consequence thing grew out of a design philosophy I was steeped in during my tabletop days and then reinforced by Richard's approach in Ultima VI – the "two solutions to every puzzle" idea. The moment that changed my design life was watching a guy play Ultima VI and solve a puzzle in a way Richard and I never thought of. I kind of decided then and there to make nothing but games designed to empower players. I always thought Serpent Isle was one of those games! Maybe I'm wrong!

At one point, Origin's RPGs seemed to be divided in two separate lineages. There were the Garriott games, the mainline Ultimas that tended to have a more "sandbox" structure. And there were the Spector games, more scripted and story-oriented. Interestingly, although the RPG genre would eventually progress towards more story-centric and scripted experiences (see any contemporary game by BioWare, Obsidian Entertainment, or CD Projekt RED), your RPGs never really achieved the same commercial success that Garriott's did. In retrospect, it seems like Origin missed out in a big way on an important industry trend. Do you think your games could have done better than they did?

Well, I certainly think my games could have sold better than they did. You have to remember, Origin at that time was split in two – not between me and Richard, philosophically (a topic I'm really going to have to think about!), but between what might be called the "A teams" and the "B teams." Richard, Chris and Andy Hollis were the "A-game" guys. They got the big budgets, built the new engines, got the bulk of the marketing and PR efforts. Guys like me were "B game" guys. I don't mean that in terms of quality – our games were just as good as the other guys. But we had smaller budgets, tighter timelines and way less PR and marketing. No doubt.

I actually liked being a "B" guy – the guys spending tons of money have all the pressure. I was spending so little no one really paid much attention to what I was doing so I got to try all sorts of crazy things. And you could be profitable selling way fewer copies than the "A" guys. It was great while it lasted. I was able to release two games a year every year I was at Origin – one internal and one external – and I always made some money for the company. I like to think I kept the lights on and the rent paid while Chris and Rich and Andy made the blockbusters. I loved it. No complaints here.

I actually liked being a "B" guy – the guys spending tons of money have all the pressure. I was spending so little no one really paid much attention to what I was doing so I got to try all sorts of crazy things. And you could be profitable selling way fewer copies than the "A" guys. It was great while it lasted. I was able to release two games a year every year I was at Origin – one internal and one external – and I always made some money for the company. I like to think I kept the lights on and the rent paid while Chris and Rich and Andy made the blockbusters. I loved it. No complaints here.

Some ex-Origin people (Denis Loubet, Harvey Smith, Sheri Graner Ray) have shared their negative opinion on the "later Origin", when it grew large and non-transparent. As Denis Loubet put it, "You could no longer know everything that was going on because everyone was in one tight clique or another and jealously guarded their turf." "Nobody was thinking about the gamers' experience", Harvey Smith once described it. Do you share that kind of sentiment about the decline of Origin Systems in its later years, even before the EA buyout?

It's hard not to share that feeling. At the time, we were all so young and we were so totally making things up as we went along. We didn't understand about the importance of company culture. We didn't get that growth had its downside. Origin certainly became more political over the years. I think that started as something good – as a healthy competitiveness among all the producers – me, Rich, Chris, Andy and so on. We all wanted to outdo the others. But that turned into something else, something less fun, less cool, as teams grew, costs went up, the cost of FAILURE went up… Sure, Origin changed. I mean, I was employee #26, I think, and when I left we had topped 300. It wasn't even possible to know everyone's name anymore. Origin was a special place – I thought I was going to retire with a gold watch from Origin – but it definitely changed. It had to change. Still, it was kind of sad to see it change like it did.

Ultima Underworld: the first "continuous-movement" first person 3D RPG

The story of the first Ultima Underworld was pretty minimalistic, and only tangentially related to the plot of the main Ultima series. Ultima Underworld 2, on the other hand, was a direct sequel to Ultima VII. It featured many characters from that game - not just the major characters that had recurred throughout the entire series, but also minor ones like Lord British's servants and staff, fleshed out with additional characterization. In general, comparing Underworld 1 with Underworld 2 is a lot like comparing Ultima 7 and Serpent Isle, in that the latter has a much greater emphasis on story. What made you decide to take that approach? Would it be correct to assume that you were more involved with the development of Underworld 2 than you were with Underworld 1?

It's funny – you say the story of the first Underworld wasn't very Ultima-like. You should have seen the first draft! Remember, that game was made by the guys at Blue Sky Productions (which later became Looking Glass Technologies) and the first pass storyline was done entirely by Paul Neurath (the company founder) and Doug Church, at that time the lead programmer. Their storyline had something to do with warring dwarves or something. Richard and I just looked at each other and silently signaled each other, "Uh… no." The story that ended up being told was supposed to exist in the Ultima universe but it in a part of it that Richard wasn't featuring in his games. The team really wanted a playground they could call their own and everyone thought that was a good idea, so it ended up being only tangentially Ultima-related.

As far as my involvement goes, I think I was there on both projects, equally – maybe a little more on UW2 because Origin did so much more work on that one than we did on the first UW game. UW really was a Blue Sky game, with me talking to Doug, who became the de facto game director, every day, basically. And an AP of mine and I took turns moving up to Boston for long stretches to make sure the game got done and that it was the game we wanted it to be. UW2 was a bit of a different story.

As far as my involvement goes, I think I was there on both projects, equally – maybe a little more on UW2 because Origin did so much more work on that one than we did on the first UW game. UW really was a Blue Sky game, with me talking to Doug, who became the de facto game director, every day, basically. And an AP of mine and I took turns moving up to Boston for long stretches to make sure the game got done and that it was the game we wanted it to be. UW2 was a bit of a different story.

In a recent interview, Paul Neurath said that Ultima Underworld 2 was a rushed product with "cut corners". That is a bit surprising, since despite having perhaps slightly less gigantic dungeon maps to explore, Underworld 2 was a rich and expansive game which didn't feel incomplete at all. Can you tell us more about that? Were there any plans for additional content in Underworld 2 that didn't make it in due to a lack of time?

Oh, man, was Underworld 2 rushed! I've always said it takes me 32-36 months to make a game. I think UW2 went from concept to ship in something like 9 months! And, of course, we increased scope dramatically as we cut our timeline back to, basically, nothing. It was insane.

The game ended up being so big I had to throw a ton of Origin resources – mostly art – on the project to augment the team out at Looking Glass. That was my first real taste of development in multiple locations. And toward the end, Doug flew down for a couple of months to work out of my office, since we had so many people on the game in Austin. Doug nearly killed himself, but the game got done. In 9 months. It was a crazy experience, I'll tell you.

The game ended up being so big I had to throw a ton of Origin resources – mostly art – on the project to augment the team out at Looking Glass. That was my first real taste of development in multiple locations. And toward the end, Doug flew down for a couple of months to work out of my office, since we had so many people on the game in Austin. Doug nearly killed himself, but the game got done. In 9 months. It was a crazy experience, I'll tell you.

Chroniclers of the history of computer roleplaying games sometimes speak of a period in the mid-1990s when the genre suffered a decline – critically, commercially, and in terms of the sheer numbers of games released. See for instance this article by Rowan Kaiser, or Wikipedia. It's probably not a coincidence that it was around that same time that you moved from Origin to Looking Glass, the latter having been focused on a genre of games that investors and publishers considered more "contemporary". As somebody who was very much at the heart of the industry during that time, can you tell us more about these events? After a Golden Age spanning from the 1980s all the way up to around 1993, how could an entire genre collapse so suddenly, across so many different companies?

There's no doubt RPG's were out of favor by the mid-90s. No doubt at all. People didn't seem to want fantasy stories or post-apocalypse stories anymore. They certainly didn't want isometric, 100 hour fantasy or post-apocalypse stories, that's for sure! I couldn't say why it happened, but it did. Everyone was jumping on the CD craze – it was all cinematic games and high-end graphics puzzle games… That was a tough time for me – I mean, picture yourself sitting in a meeting with a bunch of execs, trying to convince them to do all sorts of cool games and being told, "Warren, you're not allowed to say the word 'story' any more." Talk about a slap in the face, a bucket of cold water, a dose of reality.

If you ask me, the reason it all happened was that we assumed our audience wanted 100 hours of play and didn't care much about graphics. Even high end RPGs were pretty plain jane next to things like Myst and even our own Wing Commander series. I think we fell behind our audience in terms of the sophistication they expected and we catered too much to the hardcore fans. That can work when you're spending hundreds of thousands of dollars – even a few million – but when games start costing many millions, you just can't make them for a relatively small audience of fans.

Remember, when I started, "going gold" didn't mean "shipping a game" – it meant you sold 100,000 copies. And when you did that, you went and bought yourself a Ferrari. By the mid-90s, 100,000 copies was a dismal failure. We had to reach out beyond the 100,000 core fans. And none of us did a very good job of that, at the time. Luckily, we figured it out – or started to – later on…

If you ask me, the reason it all happened was that we assumed our audience wanted 100 hours of play and didn't care much about graphics. Even high end RPGs were pretty plain jane next to things like Myst and even our own Wing Commander series. I think we fell behind our audience in terms of the sophistication they expected and we catered too much to the hardcore fans. That can work when you're spending hundreds of thousands of dollars – even a few million – but when games start costing many millions, you just can't make them for a relatively small audience of fans.

Remember, when I started, "going gold" didn't mean "shipping a game" – it meant you sold 100,000 copies. And when you did that, you went and bought yourself a Ferrari. By the mid-90s, 100,000 copies was a dismal failure. We had to reach out beyond the 100,000 core fans. And none of us did a very good job of that, at the time. Luckily, we figured it out – or started to – later on…

We are grateful to Warren Spector for taking his time to answer our questions.